IN THE SHADOWS

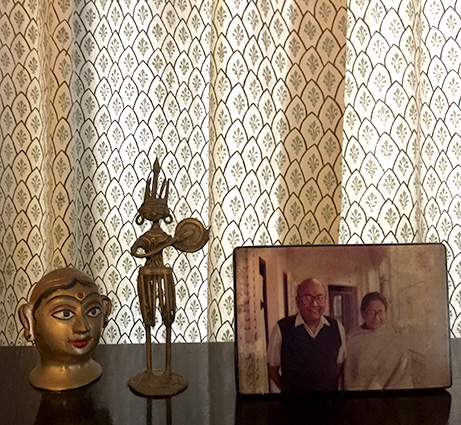

In memoriam Asit and Sreela Sen

Once upon a time, there was a fine lady in Calcutta whose conversation was always vibrant and intelligent. A vivacious woman, avid for knowledge; she invariably added a pinch of giggle to her frequent bursts of laughter. There was something about her that was like a plant, an ever elegant, convoluted vine climbing unstoppably upwards.

Like vines, she needed a prop in order to make her way to the sun. It took me only a few hours to discover that she was solar, no doubt, as much as her husband was lunar; she a solar prominence, he like the tide at slack water, moving almost imperceptibly. The wife, dynamic and evolving; the husband, self-contained, and motionless in his bearing.

Portable Kalis, Kalighat, Calcutta

On one of our trips to India she suggested we visit Shantiniketan, three hours away, and generously invited us to stay in her bungalow there. That first visit took place in January, the month to visit Bengal if one wants to enjoy un-Christian Christmas -our favourite treat in India. As we discovered, this was also the month to enjoy the little jewel of a garden that she was growing there, now in full bloom. Such a medley of colours, within a perfect, elongated rectangle, seemed to me very much like the incarnation of her own lively curiosity and the art of her self-made conversation. All the creatures that swarmed over that small portion of land were linked, interrelated, and I would even say that their sounds were very much like the hushed whispering of love. Somehow, the colours too talked to each other, so much so that whenever I contemplated the garden at its busiest I could listen to, and make resound in me, the many non-spoken, non-mammal and non-animal degrees of communication that exist on earth. Grown with care, love and elation, this garden had come to represent the gardener’s own vision of a family.

The main room in the bungalow, Shantiniketan

When years later we visited Shantiniketan again it was during Monsoon and the only trace of the garden was a patch of bare land. The burgeoning life of its own that we so well remembered was now gone and probably because of this I noticed for the first time a tree, next to the parterre; there it stood, placidly and apparently minding its own business, which is a rare gift in itself. At most, every now and again some of its whimsically crafted dead leaves would detach themselves and fall onto the garden below. Watching the leaves waft down, the image of the husband of this lady of Calcutta came to my mind. I wondered then to what extent he had contributed to the immense happiness of such a joyous wife and, therefore, to the beauty of her garden.

Interior, Calcutta

One day some friends who lived in the outskirts of the village invited us to watch a performance by Bauls. The group consisted of two men and a girl, all extremely thin and slender, their eyes as bright as diamonds, probably under the effect of bhang and long days of joyful wandering. Their intense saffron-coloured garments made them look as though they were ablaze: human flames in a landscape of emerald green and golden dust.

We lay outdoors on a kilim, swathed by the light of sunset, close to an enormous pond where buffaloes submerged with pleasure. I asked our hostess to be so kind as to translate some of the lyrics. One song caught my attention; called Life before life it was the story of an egg cell and a sperm cell before they meet. The idea of “human life” not only as a creation “ex-novo» but as a dramatic metamorphosis as well as preservation of previous forms of life made me unexpectedly happy and oblivious to the fact that I had started to scratch my shoulders.

Elaborated togetherness

A spider must have bitten me on the back while I was entranced by the voices and dances of the Bauls. I felt no immediate pain but my skin seemed to be boiling. Luckily enough, someone knew what to do: “When back at ‘your’ place go into ‘your’ garden and reach for some leaves from the first tree by the entrance; then leather them into a paste and spread it on your back.” And so I did and soon the burning of my now Pollock-like skin died away.

In and out

That night, as I lay reading on a deckchair, with the main doors of the bungalow wide open onto the garden and the fan rotating soothingly above me, I felt that a bond had been created between the tree and myself. «This bond has now the quality of a caress», I thought, «like the velvety wave of air coming from above». And then I made the link between that tree and the lady’s husband. I saw that although motionless, the tree imperceptibly protected the garden ephemera, and myself, from evil. It was a medicine tree. Later on that same night a black scorpion peacefully crossed the room, avoided all the obstacles in its way -my feet included-, and disappeared through the open doors into the garden. I remembered again the cosmos of petals, stems, insects and other animals that buzzed out there in winter… But now, all that remained was a deep fast shadow, like that scorpion moving into the night, and a rhapsody of sounds. I realised that what I call happiness has to do with composing and elaborating togetherness and that even if families are not aware of it they embody togetherness and secrete the instinct of reunion.

Togetherness…, and a giggle!

Now the room was lit only by a small candle. Abstract, shadows flickered on the wall. Out in the dark I could just make out the medicine tree in the foreground slowly merging with the blackness. It looked at first as though the night had blurred its shape almost completely. But in a fantastic living trompe l’oeil, I somehow saw it silently creeping into the house. He wanted to talk to us too, or maybe just whisper something into our ears, or embrace us.

The temple of the planets, Calcutta

Fantasising about the ghostly, aerial embrace of the medicine tree I imagined then the embrace of that husband, a man in the shadow. Maybe his was a clumsy embrace like the one I was receiving now from the medicine tree, maybe no embrace at all but I was clearly aware of the presence of an unthreatening and caring adult, a steady observer, a silent lover… and a father too who, imperceptibly, had extended his roots well beneath the garden of the family in order to weave until the end a dream of happiness.

Krishna stealing the butter

El sistema de control de la información que construyó el imperio soviético es muy parecido al que rige ya hoy en el ámbito occidental, afirmó Lydia Cacho, solo que entonces era mucho menos sofisticado. Autora de Los demonios del Edén, su escalofriante obra sobre la pornografía y la prostitución infantiles, Lydia Cacho insiste en que ella habla de todo lo que vive y de lo que sabe. No le dan trabajo en ningún periódico en Méjico, y al decir esto está, obviamente, haciendo ver que hay, al menos, dos tipos de periodistas.

El sistema de control de la información que construyó el imperio soviético es muy parecido al que rige ya hoy en el ámbito occidental, afirmó Lydia Cacho, solo que entonces era mucho menos sofisticado. Autora de Los demonios del Edén, su escalofriante obra sobre la pornografía y la prostitución infantiles, Lydia Cacho insiste en que ella habla de todo lo que vive y de lo que sabe. No le dan trabajo en ningún periódico en Méjico, y al decir esto está, obviamente, haciendo ver que hay, al menos, dos tipos de periodistas.

No puedo olvidar la mirada ni la fortaleza de esta mujer, que irradia vitalidad y convicción y a la que protege el halo del guerrero que lucha por la vida -la suya y la de los más indefensos-; ni la actitud imperturbable ante el designio que la mueve. Es la misma fuerza que anida en sus ojos; la que, después de mirar, despliega por escrito en el testimonio preciso, implacable, también amoroso, de quien se atreve a poner en palabras lo que sabe y lo que vive.

No puedo olvidar la mirada ni la fortaleza de esta mujer, que irradia vitalidad y convicción y a la que protege el halo del guerrero que lucha por la vida -la suya y la de los más indefensos-; ni la actitud imperturbable ante el designio que la mueve. Es la misma fuerza que anida en sus ojos; la que, después de mirar, despliega por escrito en el testimonio preciso, implacable, también amoroso, de quien se atreve a poner en palabras lo que sabe y lo que vive.

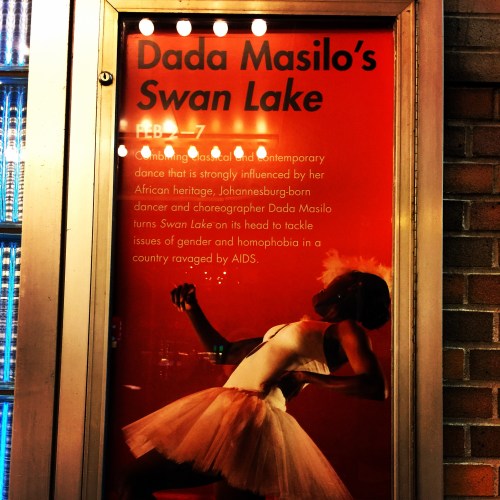

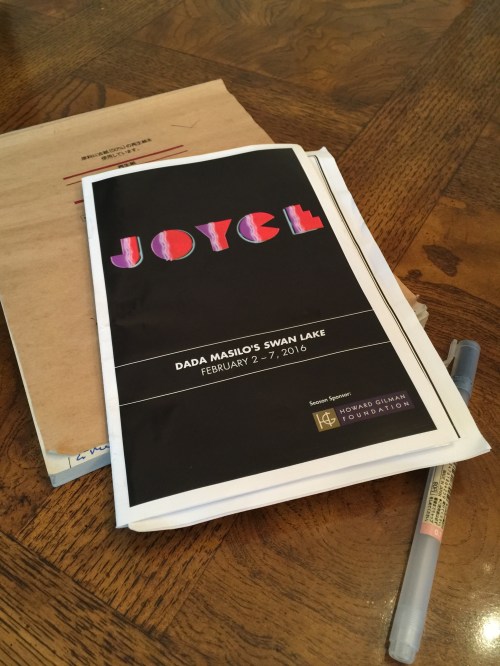

Al principio puede parecer la gracia de una coreógrafa que imita lo que otros se inventaron con gran éxito. En este caso, nada más ni nada menos que el ballet El Lago de los Cisnes, con música de Piotr Tchaikovsky y coreografía de Marius Petipa y Lev Ivanov, estrenado ya hace más de un siglo. En la era digital de internet priman tiempos cortos e inspiraciones fugaces; todo suele ser mucho más breve de lo ya hecho por otros -entre otras razones, y acaso la más importante, por la posibilidad real que disfrutamos de poder ver casi todo lo que hacen o han hecho los demás, y en la pantalla de un ordenador. Proliferan la imitación, la fragmentación y cita des-contextualizada (a menudo en el límite de la apropiación), la reducción y el resumen de lo ya hecho anteriormente por otros para fabricar a partir de ahí la nueva obra o trabajo. Predomina lo que el lenguaje callejero tilda de «refrito». A esa razón atribuyo mi desconfianza primera.

Al principio puede parecer la gracia de una coreógrafa que imita lo que otros se inventaron con gran éxito. En este caso, nada más ni nada menos que el ballet El Lago de los Cisnes, con música de Piotr Tchaikovsky y coreografía de Marius Petipa y Lev Ivanov, estrenado ya hace más de un siglo. En la era digital de internet priman tiempos cortos e inspiraciones fugaces; todo suele ser mucho más breve de lo ya hecho por otros -entre otras razones, y acaso la más importante, por la posibilidad real que disfrutamos de poder ver casi todo lo que hacen o han hecho los demás, y en la pantalla de un ordenador. Proliferan la imitación, la fragmentación y cita des-contextualizada (a menudo en el límite de la apropiación), la reducción y el resumen de lo ya hecho anteriormente por otros para fabricar a partir de ahí la nueva obra o trabajo. Predomina lo que el lenguaje callejero tilda de «refrito». A esa razón atribuyo mi desconfianza primera. No voy a prodigarme en una crítica honda y concienzuda porque posiblemente no haya para tanto esta vez. Además, ya he escrito sobre este ballet y sobre cómo, en mi opinión, lo que ocurre es que los cisnes no atinan a salir del armario (una lectura como muchas otras). No me cabe duda de que, insertado en la cultura rusa por un par de hermanos homosexuales, el lago de los cisnes o, mejor dicho, los cisnes del lago, guardan un simbolismo potencialmente tan poderoso como una bomba atómica. Muy especialmente en la Rusia de hoy. El análisis o desciframiento de ese simbolismo es un trabajo proceloso y lento, y en ello estoy desde hace años, desgranando poco a poco lo que pienso cada vez que veo una versión nueva de este lago del que los cisnes no pueden salir. Me pregunto desde hace décadas qué tendrá este lago.

No voy a prodigarme en una crítica honda y concienzuda porque posiblemente no haya para tanto esta vez. Además, ya he escrito sobre este ballet y sobre cómo, en mi opinión, lo que ocurre es que los cisnes no atinan a salir del armario (una lectura como muchas otras). No me cabe duda de que, insertado en la cultura rusa por un par de hermanos homosexuales, el lago de los cisnes o, mejor dicho, los cisnes del lago, guardan un simbolismo potencialmente tan poderoso como una bomba atómica. Muy especialmente en la Rusia de hoy. El análisis o desciframiento de ese simbolismo es un trabajo proceloso y lento, y en ello estoy desde hace años, desgranando poco a poco lo que pienso cada vez que veo una versión nueva de este lago del que los cisnes no pueden salir. Me pregunto desde hace décadas qué tendrá este lago. Y ésta versión, firmada por Dada Masilo -quién es, a la vez, coreógrafa y bailarina de su propia obra-, me llamó la atención. Nacida en Soweto, de raza negra, y defensora de los derechos de los homosexuales -muy especialmente en África- su versión seguramente revelaría algo nuevo. Efectivamente, muchos elementos en su danza son inesperados y poseen mucha fuerza. Especialmente el humor, omnipresente también en el escenario, y que fluye en gran parte a costa del ballet clásico: tal vez demasiado fácil pero bien dosificado. La representación dura exactamente una hora y 5 minutos, es compacta y no deja indemne pues trae tanto el ulular como los tambores de África al helado mundo del ballet clásico que, por circunstancias históricas y culturales, se forja de la mano de varios franceses en San Petersburgo, maestros que trabajaron para el ballet imperial de los últimos zares durante el siglo XIX.

Y ésta versión, firmada por Dada Masilo -quién es, a la vez, coreógrafa y bailarina de su propia obra-, me llamó la atención. Nacida en Soweto, de raza negra, y defensora de los derechos de los homosexuales -muy especialmente en África- su versión seguramente revelaría algo nuevo. Efectivamente, muchos elementos en su danza son inesperados y poseen mucha fuerza. Especialmente el humor, omnipresente también en el escenario, y que fluye en gran parte a costa del ballet clásico: tal vez demasiado fácil pero bien dosificado. La representación dura exactamente una hora y 5 minutos, es compacta y no deja indemne pues trae tanto el ulular como los tambores de África al helado mundo del ballet clásico que, por circunstancias históricas y culturales, se forja de la mano de varios franceses en San Petersburgo, maestros que trabajaron para el ballet imperial de los últimos zares durante el siglo XIX.

Lo esencial, en mi opinión, de este ballet, y de prácticamente la mayoría -si no de la totalidad- de las versiones que he visto, es que las víctimas de la opresión y los protagonistas de la represión y la injusticia lejos de ser minorías son mayorías más o menos silenciosas. Pese a lo que pueda pensarse respecto a la trama del Lago, por un lado, y, por otro, respecto a la forma en que los medios reflejan el maltrato a las minorías como un problema prioritario y casi único (homosexuales, judías u otras minorías religiosas, o de una una raza respecto a otra), la víctima es una mayoría; una mayoría que está encerrada en ese lago bajo el poder no ya de una minoría sino de un conjunto muy reducido de individuos. Y eso tan sencillo -que parece que hemos dejado de ver o que no queremos ver-, Dada Masilo lo representa con una gracia y una originalidad sensacionales.

Lo esencial, en mi opinión, de este ballet, y de prácticamente la mayoría -si no de la totalidad- de las versiones que he visto, es que las víctimas de la opresión y los protagonistas de la represión y la injusticia lejos de ser minorías son mayorías más o menos silenciosas. Pese a lo que pueda pensarse respecto a la trama del Lago, por un lado, y, por otro, respecto a la forma en que los medios reflejan el maltrato a las minorías como un problema prioritario y casi único (homosexuales, judías u otras minorías religiosas, o de una una raza respecto a otra), la víctima es una mayoría; una mayoría que está encerrada en ese lago bajo el poder no ya de una minoría sino de un conjunto muy reducido de individuos. Y eso tan sencillo -que parece que hemos dejado de ver o que no queremos ver-, Dada Masilo lo representa con una gracia y una originalidad sensacionales.